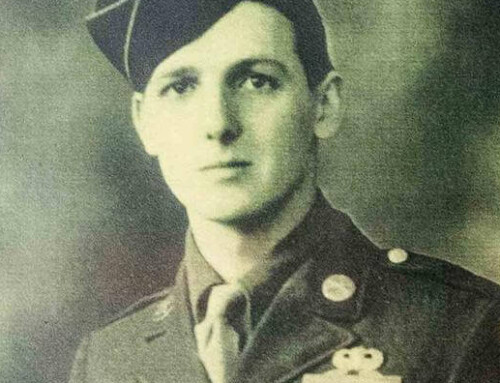

Shaffer was a World War II veteran, who, in 1948, became the first person to walk the entire Appalachian Trail. He was so picky about gear that he ditched his own cumbersome tent, sleeping in a poncho for months instead. He was particularly enamored of his Russell Moccasin Company “Birdshooter” boots, which bore him all the way from Georgia to Maine. (By contrast, modern through hikers may chew through two or three pairs of newfangled Gortex contraptions.) He paused often to sew, grease and patch his footwear, and twice had the soles replaced at shops along the route.

Shaffer was a World War II veteran, who, in 1948, became the first person to walk the entire Appalachian Trail. He was so picky about gear that he ditched his own cumbersome tent, sleeping in a poncho for months instead. He was particularly enamored of his Russell Moccasin Company “Birdshooter” boots, which bore him all the way from Georgia to Maine. (By contrast, modern through hikers may chew through two or three pairs of newfangled Gortex contraptions.) He paused often to sew, grease and patch his footwear, and twice had the soles replaced at shops along the route.

The boots today are still redolent of 2,000 miles of toil. (Shaffer frequently went without socks.) “They are smelly,” confirms Jane Rogers, an associate curator at the National Museum of American History, where these battered relics reside. “Those cabinets are opened as little as possible.”

Perhaps the most evocative artifact from Shaffer’s journey, though, is an item not essential for his survival: a rain-stained and rusted six-ring notebook. “He called it his little black book,” says David Donaldson, author of the Shaffer biography A Grip on the Mane of Life. (Shaffer died in 2002, after also becoming the oldest person to hike the whole trail, at age 79, in 1998.) “The fact that he was carrying those extra five or six ounces showed how important it was to him.”

First and foremost, Shaffer, who was 29 at the time, used the journal as a log to prove that he had completed his historic hike. The Appalachian Trail, which marks its 80th anniversary this summer, was then a new and rather exotic amenity. Some outdoorsmen said that it could never be traversed in a single journey.

But the journal is about more than mere bragging rights. “I’m not sure why he needed to write so much,” says archivist Cathy Keen of the National Museum of American History. Perhaps Shaffer tried to stave off the loneliness of the trail, which was not the well-trafficked corridor that it is today. (About 1,000 trekkers through-hike each year, and two to three million walk portions of the trail annually.) Shaffer also sang to himself a lot, loudly and, in his opinion, poorly. An amateur poet, Shaffer may have been attempting to hone his craft: He jots a few rather forced and flowery nature poems in the notebook’s pages.